Jo

I was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, a child of white privilege during the most brutal years of the apartheid era. I was raised largely by my three black nannies in our sprawling suburban home. My nannies were named Lily, Anna and Johanna.

They were all from the local Tswana tribe, and I learned to speak bits and pieces of Tswana as a child, especially how to recite the formal greetings which was very important etiquette in Africa. Lily was usually referred to as Gohgoh, which meant grandma in Tswana. She was like a grandmother to me, although I delighted in playing childish pranks on her, like switching salt for sugar in the containers on the kitchen window sill, or taunting her with a chameleon captured from the garden. She used to quarrel often with my father, whom she probably saw as a young upstart. He fired her on more than one occasion, but she simply refused to leave because our house was her home too. Gohgoh stayed on, even when she was too old to work, until she eventually moved away to spend her last days on a smallholding in the rural tribal area which the government identified as the homeland. Anna was in her twenties when she worked for us, when I was a little boy, and after she left, Johanna, who was only about eight years older than me, was my nanny. She was my nanny until I did not need a nanny any more, but she did not retire until she was close to sixty, and, long after I left home, she took care of my parents, whom she always called Mommy and Daddy. My father made sure that she had a pension, and investments to pay for her retirement.

The servants lived in quarters adjacent to our house, with their own bathroom, and small bedrooms with a maroon slab floor, which they polished daily with wax polish. They were trusted with keys to the house, which, in Africa was always locked from the inside at night. Burglaries were common, and some nights, from the servant’s quarters, they could hear housebreakers and car thieves scraping around outside the premises. Once in a while, a car radio was stolen. Everybody in the household was aware of the drawer in the nightstand where my father kept his pistol.

In the morning, the servants used to unlock the back door to get inside before we woke, so that they could prepare breakfast. They used the same kitchen to cook their own food after they had cooked for the family. Their staple meal was sour porridge or pap – something like grits – served with gravy made from chopped tomatoes. On special occasions, the sour porridge was served with meat. They always ate the pap with their hands from metal plates. Sometimes, they cooked foul-smelling spinach called morrocho, which pervaded the house with fumes. In the evenings, they served us steaks or roast beef or chicken a la king in the dining room, and my mother offered them the leftovers when we had finished eating.

During my school years, Johanna woke me every morning, and laid out my clothes for the day. For breakfast I ate cereal, or soft-boiled eggs from a silver egg-cup. I would often turn the egg upside-down in the egg-cup after I had scooped out the yolk, pretending that I had not eaten it, but Johanna was never fooled. She prepared sandwiches for my school lunch, cutting off the crusts, and she packed my lunchbox. She made my bed, tidied my room, washed and ironed my clothes and polished my shoes. There was a hot meal waiting for me when I came home. She knew my favorite was spaghetti bolognaise, with a cola tonic or cream soda to drink.

In the afternoons, we would sit on the front lawn on a brightly-colored blanket spread beneath the vivid blossoms of the Jacaranda tree. She would watch me at play. The radio filled the yard with tinny music from the Tswana station. Lazy hours rolled by in the dappled shade. An ice-cream vendor on a bicycle pedaled past, ringing his bell. Women from the countryside, balancing large bundles on their heads, sold raw sugar-cane or ears of corn called mielies in the street. Johanna’s friends, who worked as maids in neighboring houses, would lean over the fence so they could share stories. I loved the babble of her language, with its strange sounds, sing-song rhythms and breathiness. I loved venturing into the alien world of her room, with the bed raised high on bricks to prevent an evil supernatural pygmy named the Tokolosh from climbing on top of her in the middle of the night. I loved the crazy, frenetic melodies on her radio, and the True Africa photo-comics, which she let me borrow. There was Samson, an African superhero, and Chunky Charlie, a magical detective with a baffling overcoat that contained everything from bulky telephones to candlesticks.

Food, language and every aspect of the culture made the black world so unlike the white world. Our lives were intertwined but starkly different. As a child, I lived in both worlds, richer for the experience. Our mutual affection was deep and genuine. There was never a hint of racism, suspicion or antagonism among us. In my parent’s house, a racial epithet was an unthinkable crime punishable with a mouth full of soap.

Apartheid was simply the reality around me. It was normal; there was no objective frame of reference. As I grew up and was fortunate to travel outside South Africa, I began to question it more and more. When I became a teenager, I put protest posters on the walls of my room, wrote angry poetry and listened to the songs of Rodriguez. I understood that South Africa was not a free country, and dreamed of one day traveling to America.

In America, people could come and go as they pleased, read and say whatever they desired, and legal rights were guaranteed. In South Africa, movements were monitored, books and films were censored or banned outright, and suspects could be jailed without cause for indefinite periods of time. The press was hounded. The authorities could do no wrong; even harsh interrogations were permitted in the name of public safety. A secret government bureaucracy was created; it was called the Bureau of State Security, but it was known by its chilling acronym, BOSS.

At the age of seventeen, I was drafted into the military, but because the South African Police was short of manpower to deal with the growing unrest in the country, I was reassigned into a special program to serve as a beat cop in Johannesburg. It seemed like an easy way to avoid desert warfare on the volatile Namibian border, because after a training stint at the Police College in Pretoria, I would be allowed to live at home and work shifts at the local police station.

With a group of nervous, smooth-faced teenagers, I was issued a train ticket from Park station in downtown Johannesburg for the forty-minute railway journey to Pretoria. My parents were there to see me leave, and an avuncular recruiting officer with a jolly moustache walked up and down the platform making sure that we were all on board. There was a convoy of Bedford trucks waiting to meet us when we arrived, and a crew of twenty-year old supervisors who began yelling and cajoling us as soon as we were in their hands. We drove through the streets of Pretoria loaded on the back of the open vehicles, scared to speak. The Police College lay in an industrial area of Pretoria, sandwiched between a green-roofed mental hospital on one side, and the smoke and sparks of a huge steelworks on the other side. It was whites-only; there were separate police colleges for black, Indian and mixed race cadets. We received instruction in weapons, combat, drilling, physical education, first aid, crime detection, and the rudiments of the legal system. At the end of the college period, we were sent into the bush for six weeks, so that we would also have basic training as soldiers. After that, I was assigned to a police station in Johannesburg.

My partner was a black policeman named Victor Nyambeni, a member of the Venda tribe, who had scarification from tribal rituals carved into his cheeks. He was a ferocious warrior, and I was a green recruit. He protected me on patrol, and we became close friends side-by-side on the graveyard shifts. We were empowered to enforce the law on black and white alike. We saved people in distress; there were car accidents, fires, crime victims. We arrested murderers, rapists and thieves. We recovered stolen property, and returned it to its rightful owners. We made sure our neighborhood was safe. We were also compelled to enforce apartheid laws, mostly to do with restrictions on movement. Every black person was required by law to carry a permit, called a pass book, stamped with permission to be in Johannesburg; blacks were under curfew, and could not be on the streets after eleven pm without a night special; interracial marriages or sexual relations were forbidden. Whenever Nyambeni apprehended a black man from another tribe, there could be violence. I had to intervene when he water-boarded a detainee, which was a standard method of torture used to extract information or simply for sadistic sport. Accidents could happen.

There was no place for soft sensibilities for a policeman on the uncertain streets of Johannesburg, still one of the most dangerous cities in the world. Kind treatment of prisoners was seen as weakness, by criminals and fellow cops alike. Sympathy was dangerous. I toughened up like the hardened men around me.

When I came home in my police uniform, Johanna’s neighborhood friends, who had leaned over the fence when I was a child, trembled in fear.

As soon as I was old enough, at the age of twenty-one, I went to live in Europe. After a few years, in my early twenties, I received a visa to study in America. I married an American citizen, and was proud to stand before a judge at the Los Angeles Convention Center, with five thousand other immigrants, and swear the pledge of allegiance to my new country. I felt that I was free at last.

I will never forget being in my California apartment when Nelson Mandela was released from prison. I watched the headlines on CNN all through the night. As I was growing up, when people - curious about my accent - learned that I was South African I was vilified and attacked as a racist so frequently that I sometimes claimed to be Australian; now, wherever I went, I was embraced and congratulated.

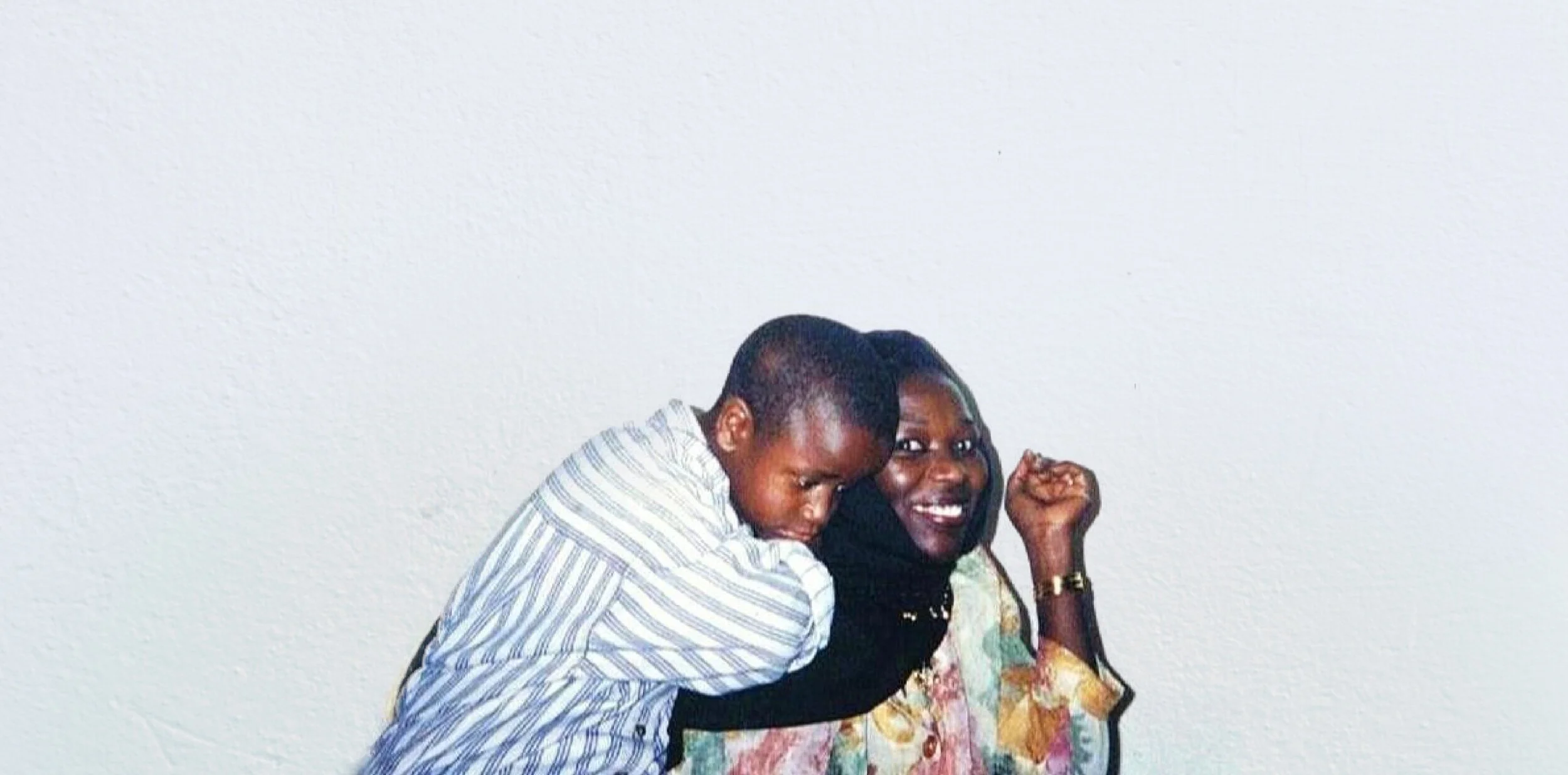

I returned to South Africa often after liberation. Johanna still worked for my parents, and we hugged and joked and exchanged presents whenever I visited. I gave her a statuette of the Statue of Liberty. She tested me on my Tswana vocabulary which I still remembered. I never forgot the courteous way of exchanging the African greetings. Her young Tswana son, Tembi, played under the Jacaranda tree on the lawn of my parent’s home with my American boy, Jake.

Our children faced a future so different from our history.

In South Africa today, there are many interracial couples, gay marriage is nationally recognized, human rights and freedom of speech are guaranteed, the constitution is upheld as a testament to civil rights. In America, where I chose to be free, there is a vast Department of Homeland Security with sweeping powers, much like BOSS when I grew up; dissidents can be held in indefinite detention; water-boarding has been enforced; movements and communications are under surveillance; there is open racism; and people are listening to the songs of Rodriguez.