Weaving Worlds

I stepped into Ana María Velasco’s studio in Greenpoint and I found myself transported, shrunk in the presence of monumental canvasses beaming with colors laced into intricate patterns. Daunting peaks of distant mountains emerge from two large landscape paintings — Luna Llena and La Sierra. Ana Velasco has displayed them only for my visit: “I usually keep them turned toward away against the wall while I’m working,” she tells me, “so I’m not influenced by them.” Her works have been featured in solo shows at the Colombian Consulate in New York City and the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia in Cali, Colombia. And now, across from a wooden desk blanketed with stacks of cut-outs, I could see her current work taking shape, an enormous canvas mounted directly on the wall, dominated by the pale outlines of mountain peaks looming over an expanse of vegetation. When she offers me a cup of tea, I do not want to set it down anywhere. Not when I was just inches from Velasco’s paintings, imaginary landscapes with unmistakable fragments of reality and history woven into the fabric of plants and mountains.

What can you tell me about your current projects? It looks like you’re in the middle of painting something big here. Would you describe your process?

I’m working on these mountainscapes inspired by the Sierra Nevada Santa Marta, the largest coastal mountain range in the world, where I lived along the north coast of Colombia. I am connected to it on a personal level, but the viewer does not have to know where it is. It is a universal place.

I work directly on the canvas and create compositions in an intuitive way. I do not have a fixed plan, I do not make sketches, and I work on various paintings at the same time. I move from complex narratives and compositions on large scale canvasses, to small paintings with simple images. The themes of my small paintings come out of the large landscape. Once taken out of the context, some of these images express their own voice and individuality. They are no longer anonymous and become their own protagonists. Some I will not incorporate into the large piece but nevertheless they are coming from it. In the past it was the other way around, I would create the landscape through the images of the people and the narrative.

I collect images from Colombian newspapers. Although I am making a conscious attempt to step away from being associated only with Colombian imagery. I do not want to be seen only as a Latin American artist. I take inspiration from my personal history, I am interested in the history of painting and how my story fits in.

I am interested in the way you show people in these large landscapes. The human figures are monochromatic and many seem to be anonymous or universal. Then others seem to represent specific people, like in La Sierra. Would you tell me about who they are?

Yes, there are some historical figures from Colombia like Simón Bolívar, Policarpa Salvarrieta, Caldas the Wise, Camilo Torres. The last two are my direct ancestors. Caldas the Wise was an engineer, naturalist, mathematician, geographer, lawyer, journalist and inventor. He was part of the Humboldt expedition and surveyed the biology of Colombia. I grew up hearing my dad share stories of his life. Camilo Torres was a founder of the early independence movement against Spanish rule. They were precursors, or predecessors of the independence movement in Colombia. They were both executed along with many many other people who were resisting colonial rule.

San Ignacio de Loyola is also in this painting. He is the founder of the Jesuit order had a great impact on me as a child, not only in Colombia but also in Nicaragua. During the time of the Nicaraguan revolution many of my teachers were Jesuits influenced by liberation theology. They advocated equality and service. They were open minded, they were artists and poets. The line between art, spirituality and religion was not as rigid as I see it here in this country. I wanted to be a nun when I was seven years old. Because they were so cool! They were funny, they were lively and passionate.

What do the more universal figures mean to you, like the athletes?

I started working with the images of soccer players about twenty years ago. I became obsessed with cutting out images of soccer players, and of bullfighters, and I’ve kept doing it! I have been collecting them along with my father. Neither one of us is that interested in these sports. I ask him to clip and save them for me, and when I see him about twice a year he has a piles of new ones. It is perhaps a way to stay connected with him. I love the movement of these male figures — so stylized, so beautiful. They fly almost like superheroes. It is an archetype but also represents a lot of things in my culture, we grow up with soccer in our skin, it’s in your soup, it’s everywhere.

It’s related to the archetype of the bullfighters, also a male figure. They’re like ballerinas moving through space. I have seen a lot of bullfights. Cali, where I grew up in Colombia, has a very important bullfight season. The first time I saw one I was ten years old, I cried and I had a complete breakdown. And then there was one season when I went and I could step back and look beyond the cruelty and brutality. It’s an incredibly violent spectacle, it’s terrible, it’s horrible, yet there is visual beauty. It has a drama like soccer, yet more flamboyant and theatrical.

That feeling of letting go of the body is amazing, and athletes seem to be able to trust that. Athletes are in tune with their bodies, there is something magical about living your life everyday as if everything depends on the moment. In one moment they are running after a ball, in another they are frozen in mid-air. There’s a different kind of painting space, a different intensity: the figure floating on a plane. Each time I paint one of these figures is a different kind of time. The way time can only exist in paintings.

The spectators, soldiers, jaguars, and plants are no less interesting than the bullfighters or soccer players. I like the idea of having a sense of democracy across my surfaces, and not so much of a figure-ground relationship. The way the background is fissured or broken up can make other kinds of figures out of things that aren’t figures. I think a lot about surface and relationships. I want these areas to be activated, to somehow have their say. Everything has to have an impact, and that gives it alloverness. There is no hierarchy to me. That is how dynamic symmetry emerges. You are being pushed or pulled.

La Sierra

What other types of people are you interested in painting, and how do they figure in your landscapes?

I paint people who interested me because I have a connection to them or because they represent something I care about. I have some images of the indigenous priests who live in this mountain called mamos or mamas; they are spiritual and political leaders of communities descendant of the preColombian Taryona people who still live in this mountain range. They consider themselves the guardians of the earth and their mission is to keep the balance of the planet. For them the Earth is a living entity, and they believe we must pay back to her whatever we take from her. If we take down a tree to build a house we have to pay back to the earth through offerings. The offerings are known as pagamentos, or payments. The mamos are trained when they are babies to understand the spiritual world which they call aluna and to make pagamentos to maintain the equilibrium of the earth.

Other paintings depict accidents, bodies, and tragedies. And groups of people viewing tragedies in a collective way. Those images are imprinted in my mind. Growing up in Colombia, I remember driving with my mom on a regular day, and driving by accidents and seeing dead bodies. Everybody looking at the dead body. Sometimes the dead body would stay on the ground a long time before the ambulance would come. I remember seeing a lot of these images as a child, people looking at a dead body, these accident spectators. Similar to the people who go to the bullfights, elegant women dressed with big hats wearing their best outfits to see this terrible thing.

It’s a multilayered reality, the way I construct the landscape or the space is not traditional, but there is depth and perspective. There are formal decision and there are decisions around the subject matter, then I try to integrate them. I do not draw before. It’s only when I am in front of the painting that I start to create a dialogue with the images, with the shapes, with the composition. That is what painting can do that other two-dimensional forms do not.

Your large paintings feature vibrant patterns, texture and geometry. Then looking at your drawings and portraiture, I am struck by the strong contour lines and negative space. Would you tell me about where the patterns and lines come from in your work?

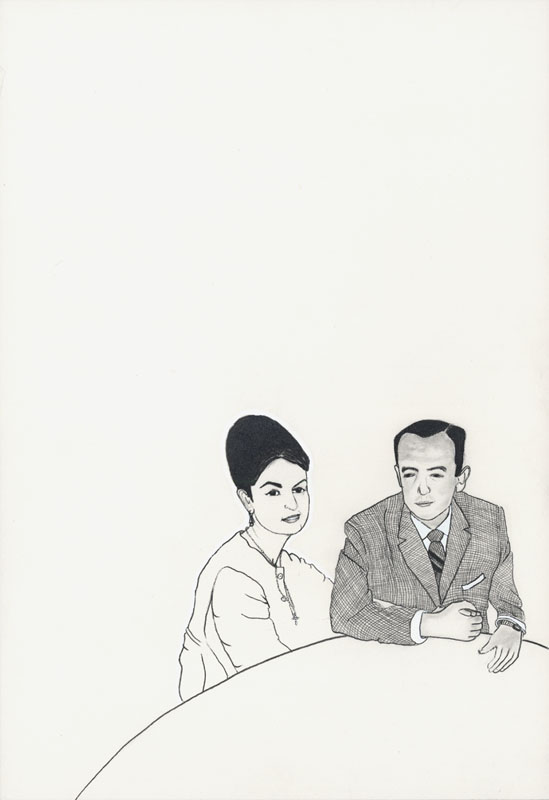

Maria Jose y Julian

Images come first, I don’t always start with a preconceived idea, but then I can go back to the work and find meaning. These clusters of people floating above the landscapes entangled in these mountains create the structure of the painting. I find meaning afterwards through the process. In La Sierra, I began painting vegetation. Along the way, I decided they should be coca plants adding another layer to that painting. I have made portraits of my friends and family. This is like zooming into a more intimate view of my life, and giving a voice to some of the people who are in the large paintings but anonymous. When I draw them in portraits they become important, and you can connect to them as individuals. Other patterns are extracted from the large paintings, to offer a more personal intimate view of the larger subject.

When I was studying in Colombia painting was not very popular. I studied at a public art school in Cali where the curriculum was designed by some of the most prominent conceptual artists in Latin America. Doris Salcedo, Luis Camnitzer, Oscar Muñoz. The focus was on sculpture, installation, photography, video art, and performance. That was my first introduction to contemporary art and I loved it. We had some drawing and painting classes, but the emphasis was on how to think critically. There was a sense of ethics, rigor, and responsibility. When I moved to the United States, painting became an act of freedom for me. It was a breakthrough, but it was also breaking away from my rigorous conceptual training which I still value.

In what context did you stop painting?

It was not a gradual thing. I had my first solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in Colombia. Although it was well-received, I felt uneasy and vulnerable. More than anything it was an existential problem — I felt I was not contributing to humanity by making paintings. I was conflicted and felt guilty for wanting to be an artist. Growing up in war in Nicaragua and Colombia, my family from both sides had a sense of sacrifice and sociopolitical responsibility. I felt I did not have the privilege to be a painter. Spending so much time alone in my studio felt very alienating. I was not part of a community of artists in New York. It was then that I decided to stop pursuing a career as an artist and I founded a 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to develop yoga programs for people affected by the violent conflict in Colombia, specifically ex-guerrillas and ex-soldiers. I went back and forth between New York and Colombia. With a group of other teachers, we taught people who worked with the affected communities: teachers, social workers, psychologists, therapists and priests.

During those years, I began to study Buddhist philosophy. I traveled through India and I spent time in silent meditation retreats in the mountains. I lived in the Colombian jungle and learned from indigenous wise men and women. It was a long process that brought me back to where I am now. Full circle. I can finally paint without having to apologize for it. I began painting again four years ago, bringing all the things I learned in those years: from the nonprofit, working with ex-combatants, living in the mountains with the mamos, practicing the discipline of yoga and meditation, teaching and working with a diverse variety of people.

What’s the name of the nonprofit organization? Were you participating as a teacher?

Neem. It’s the name a medicinal plant common in India. Yes, I taught wounded people, people without limbs, ex-combatants, children. I taught yoga to soldiers suffering PTSD. I continue to teach. It is gratifying and I learn so much from the people I have met. My sister is an activist in Colombia and she’s involved with organizations that help with the reinsertados, reintegration, and particularly she’s works with this foundation called La Fundación para la Reconciliación, Foundation for Reconciliation, and it’s now one of the most recognized foundations in Colombia for the work they’ve done around peace and forgiveness. My sister put me in contact with them. We integrated yoga into their existing programs. Then we chose participants from the communities to train as yoga teachers so they could make a living as teachers in their communities. My dream is to have Neem contribute to the extraordinary work that the Colombian-based organization Dunna has done to promote peace.

close up of “Aluna”; complete painting in the banner image

Have textile arts influenced your painting, or your process?

All of these paintings are a little bit like tapestries, human-woven textile of all these stories. It all has to work and tie together, like when you knit. I have an obsession of wanting everything to come together in a balanced way. It’s a human tapestry for me, every stitch is connected to the other stitch, everything matters even though it is chaotic, it’s connected. Although with weaving you have a purpose. I was taught to weave mochilas by the indigenous women from La Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. These handbags have a specific shape. You start the bag from the bottom, with a circle going around and around from the bottom up, and for these women it represents the universe. They put a thought into every stitch. It’s a meditation. If you show your mochila to one of these ladies they will know how you’re thinking, so they say. If it’s even and without mistakes then it shows you’re focused and thinking clearly. It connects to painting because I’m creating universes, from a thought you can create these worlds. I’m always impressed with what comes out of my paintings because I don’t really know what is going to happen. With the mochilas you know it has to end up being a mochila, yet it is a symbolic universe.

Are you an artist in exile? How have your experiences shaped the way you see political conflict in the present day?

I have always been in exile. Since I was three years old and moved to the U.S. for the first time. I was in exile when I moved to Nicaragua at five, and I was in exile when I moved to Colombia from Nicaragua at ten years old. So yes, I am now an artist in exile. I think that is why I have decided to stay here in New York. There is so much diversity that I can feel at home sometimes.

When I was in Nicaragua as a child I was very aware of what a dictatorship was, I was aware of what democracy was, that we didn’t have it. My mother could never vote in her life, ever. I developed secret codes to talk about politics on the phone with my friends when I was seven and eight years old. In school, we knew the kids who were with the dictator, or against the dictator. Politics were part of my childhood. My grandmother’s cousin was a journalist who founded the first free speech newspaper in Nicaragua. He was murdered. His death catalyzed the revolution in Nicaragua. I remember being in the airport in Medellín, Colombia. When my mom saw the news on the TV screens, she started screaming and sobbing hysterical in the airport, “they killed Pedro Joaquín!” They killed Pedro Joaquín. What happened in Nicaragua always felt very visceral, very close to me. The combat, the Cold War was happening in my backyard. Growing up, I would hear the bullets outside of my school. Sometimes we would have to stay at school until midnight when the combat had stopped down the street. I knew when my next-door neighbor was assassinated because he was an activist. It is a tiny country. My relatives were involved, and I knew it. It was a personal war, and I understood it in a visceral way. Everyone close to me was touched by it directly. It wasn’t just something you heard about on the news.

Seeing the debates two years ago in this country, I was reminded of those childhood memories. Division, polarization, power and corruption. I believe that activism can have a positive impact in our world, yet I learned early on that I could not fix my surroundings through politics. It’s the nature of this broken realm, of cycles of suffering where things repeat themselves in patterns endlessly until we wake up. Until we develop a sense of awareness.

What are you looking forward to, and what are you goals for the future?

I am committed to my art and my painting. I will continue painting these mountainscapes. Additionally I am working on a series of animals, birds, still lives, and portraits. I like to extract elements of the larger landscape and paint them individually, giving them unique character. Alternating from large complex projects to the series of animals provides me the space to paint with less effort and more contemplation.

I also want to make some work on paper again. There is always a need to go from complex situations to simple ones. From the public to the private, collective-personal, macro-micro. I would like to go to an artist residency. I need the time and space to develop ideas, and to connect with other artists and receive feedback. I have two jobs in New York and my time in the studio is limited. I hope to return to Santa Marta this winter. And I will collaborate with Dunna in Colombia to develop yoga programs they have already started.

Art for me represents freedom. It is a safe space where I can explore and make mistakes. I feel very grateful to have this outlet where I can play out my passions, concerns and interests. I will continue teaching and learning.

Jaguar