On Arrival

1982, Long Island, New York

A rubber Mickey Mouse. Red soap on a rope. Pink tile. Pink carpet in the bathroom.

Having carpeting in a bathroom is radical and royal to me.

The bread is white and must be toasted to taste like anything.

Roast beef tastes like raw meat.

I’m not used to drinking milk cold, or to the density of apple juice.

My new mother has laid out an outfit for my first day of school. The white, short-sleeved collared blouse and red plaid skirt are prim and suit me. It’s not the starched khaki pinafore and brown and white checkered blouse of my Catholic school uniform in India, but it’s close enough.

I’ve been in America 24 hours. Outside, the sun shines, but I’m not an outdoor kid. I choose to stay indoors, indifferent to the bright afternoon because it’s always sunny in Bangalore.

The kitchen and bathrooms have sinks with hot and cold water faucets. Before, my grandmother would bring hot water to me in a dented metal pot, holding it with padded rags, then pour it into a bucket of cold water. I would sit on a small plastic stool, soaping, pouring, mixing the proportions of water over a good long time. Here, I’m fascinated that I can adjust the knobs to get to “just right” in seconds. It’s not that our Bangalore bathroom struck me as unroyal; the cement floor was cool, the exposed light bulb cast grey shadows on walls that look yellow, and the steam from the dented metal pot smelled sweet, deep, and hot. But on Long Island, I get to take my first shower.

When school begins, I have a plan. I will not speak until spoken to and I will sit in the last row and hope to not be called on. The classroom is crowded with small desks, bags, puffy jackets and smells of baby powder and hard candy. My plan doesn’t last long; I know the answers to more questions than the other kids and can’t help but volunteer to break the silence.

After school, I expect my father, Appa, to be waiting. I will tell him about the pledge of allegiance and lunches on trays. In India, he gets off work at 2:00, and we go around on his scooter. Instead, I remember I must walk from the bus stop to a charming country house on our street where an unfriendly man with black curly hair and his wife with flaming blonde hair, Joyce and Charlie, live. I will spend the afternoon there until my new stepmom picks me up. Joyce yells at everyone but me. I stay in her home doing headstands in front of the TV as the 3 pm, 3:30, 4:00, 4:30, and 5:00 o’clock shows come on. Cartoons, then the Brady Bunch, then Little House on the Prairie. Some days, when my stepmom is late, I will join Joyce’s table where dinner is Spaghettios out of a can and boiled carrots.

I remember my grandmother’s sannas (rice and coconut cakes), the middles that felt like silk pillows, the edges like lace.

I remember the smell of ball point pens.

I remember two metal containers of water.

One for washing dishes. One boiled for drinking.

I don’t like egg yolks or cream in my milk.

I remember my grandmother telling me the only time she ever hit me was with a comb when I spat out my food, only to discover there was a cardamom pod in it. She felt terrible.

I remember the number four engraved in tiny metallic dots on my aluminum cup and saucer. The set belonged to my mother who was the fourth child in the family.

It’s my first weekend in America and my new mother wants me to call her “Mom.” She and my father were married four months ago after a lunch date followed by a quick engagement. My father and I made a sharp turn for a life in a new country, where my stepmother had already lived for many years. And so, for us it is as much starting a new life as it is entering her established one.

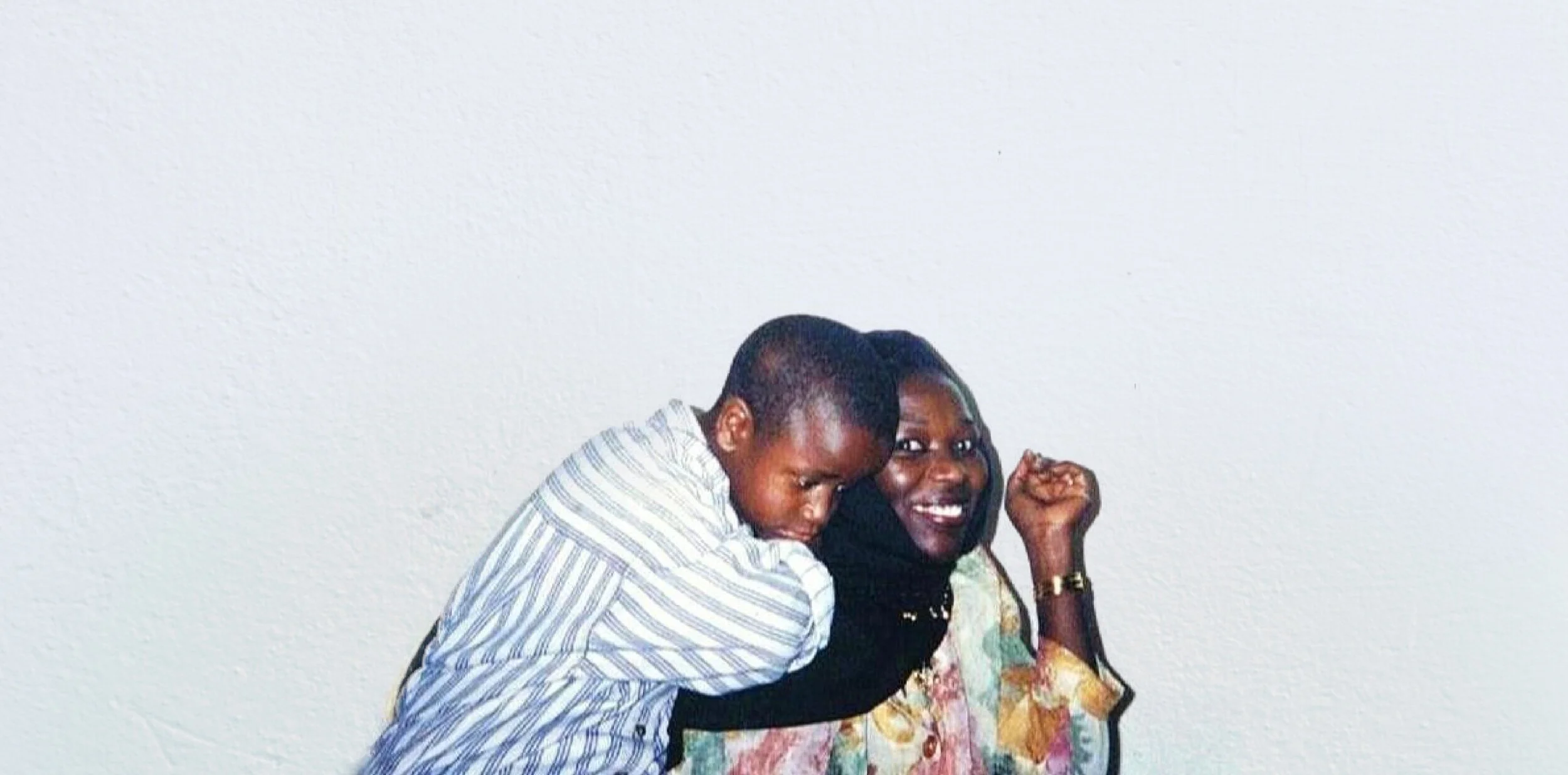

I’m faintly startled by her request, but in the moment, I don’t think to object. I called my biological mother Amma even in the prayers we said for her after she died. I called my grandmother who raised me in the seven years before I moved to America Mummy. I don’t have any siblings yet, but in a year, I will have a little sister. She will be the first in our family to be born in America, the first baby I will love. She has big, brown eyes and reminds me of a beautiful doe; and later, even into her 30’s, I will sometimes still call her Bambi. I will call my stepmother’s elderly relative who moves in to take care of the new baby and me Aunty. It will take decades before I come to terms with what juggling four titles for mother would mean to me and to the women who’ve been in those roles.

In addition to my homework, I study the television - listen to it, more than watch it. As the World Turns. The Young and the Restless. 60 Minutes. My English is perfect thanks to my anglicized upbringing in India, but I sound vaguely British-Indian. Now, I model my accent on TV anchors, the host of the evening news, Chuck Woolery. “New York.” Even those 7 letters are each recast slightly in relation to each other, the R is softer, the O has multiple sonic elements and is different sounding in “York” than in “Long Island.” I learn to form my mouth and tongue to sound generically American; for the rest of my life people will not be able to trace any Indian intonations, let alone any regional dialect or accent.

I am not Indian or American for my first Halloween. I am a witch. I can conjure magic and cast fearsome spells. I do not smile for the photos, and that demeanor, which will be admired as composure in the future, becomes my guard. I hold onto it tightly like keys jutting through the slits of a closed fist when you walk home alone at night. Alone in my room, I take the dress off the Victorian doll who forms the base of my bedside lamp and put it on Babita, my doll from home, who I’ve had with me since I was one. I take off Babita’s brown wool pants. They won’t do here.

Here is not “home” yet and Bangalore is fast slipping from memory, though I replay images every night before I go to sleep - the little red plastic dog on my grandmother’s shelf, the butter tray, the jar of kids’ calcium tablets with a poodle’s face, the patch of lemongrass outside our front door.

My grandparents, my mother’s side of the family, and I are all Mangaloreans. My grandparents make homemade wine and let their children drink it with dinner. They eat pork and have affectionate names for the fat, gil gil. They kiss on both cheeks when greeting and saying goodbye, never namaste. The women in our neighborhood as comfortable in saris as they are in mini-dresses, but they shun bindis and the red powder worn in the part of the hair by married women. Mangalorean kids mostly go to Jesuit schools, St. Joseph’s, St. Aloysius, Mount Carmel, and families attend specific churches, St. Patrick’s and St. Francis’ cathedral in Bangalore. In food, in dress, in marriage, birth, even in death, we are different. We are used to being different. I’m different twice in America, once as an Indian, and once more as an Indian Christian.

My father and I still say bedtime prayers. But my stepmother is not of our faith. She rings a bell and holds her hands together facing the linen closet and a shelf holding miniature gods. According to how Americans think, she is more Indian than we are. But she has lived in America longer, so according to how I think, she seems more American than we are.

There are no photos of my mother in our new house. My father fails to suggest one or two can be in my room. I fail to realize that option too.

I learn to play the guitar. I choose my sheet music carefully. Something for the past, John Denver’s Country Roads, a song I sang with my father riding on a scooter with him through the streets of Bangalore, and something to please my new musical tastes in America, the start of a love for “new wave”, the Human League’s Don’t you want me, baby?

Some nights, I cry hard into my pillow. It mutes the sound; it’s warm and wet. I cry when I feel misunderstood. I cry when I feel I’m losing the smells, the colors, the touch of Bangalore, my grandmother’s gold bangles, the soft mole on her back that I played with as we fell asleep on the twin bed we shared. My stepmother says that when I cry my father gives in too easily. I make a mental note to tell her crying is a sign of strength, though I never do. Decades later, I will see her cry when her mother dies, and a second time when, in an LA coffee shop, she will tell me she wishes she had done some things differently as a parent. I remind her of all the great things she did do. I am pregnant in this conversation, about to be a mother, and I already know I will make countless mistakes.

My stepmother is my introduction to America and I am her introduction to being a mother. We are both immigrants in that sense, me in my new country, she in her new daughter’s life.

For now, I am waiting. Intezar. It’s one of those Hindi words that doesn’t translate perfectly into English. There’s a whole host of these in different languages, a testament to how much more there is to say, always. Technically, Intezar means ‘waiting’—but it’s a specific kind of waiting. Full of desire, and yearning, but it’s likely for something that can never be, or someone who will never arrive. It is a lover’s promise. I will wait for you. Forever, if I have to. The word is a cousin of longing, a slightly older, more noble relation, who may have more time on his hands, but is no less hungry. After all, the word was born in a place where there is such a thing as protecting your children from hope. But it’s also from a place where the Kamasutra was written, where the erotic temples of Khajuraho were built by human hands, where desire is an art - something to be experienced as an end in itself. I feel this way about the city I belonged to but left behind. I feel this way also about a place in my dreams, that I haven’t found yet, where I might someday fit again.

We go apple-picking in Vermont, play tennis at the neighborhood courts, eat Thai food in Queens. I hear the sound of the Long Island Railroad, that we call the LIRR. Its long whistle reminds me of the train I took when I left Bangalore for the international airport in Delhi where we’d board a Lufthansa flight for America. As the train pulled away from the Cantonment Railway Station near the house I grew up in, it took a few minutes before I was unsteadied by a sharp pain in my chest. I remember it as a physical tearing and I shouted for my grandmother. The train kept moving and my father consoled me. I quietened eventually, but I would embody that feeling of tearing forever. For now the LIRR would take me to the mythical city of Manhattan, one step closer to the mainland, a city that would inspire a thousand journeys until I got to the other side of this vast country. I couldn’t have known this then, that the port of my arrival in America wasn’t final, but just a first stop. That when I’d see the palm trees and feel the sun of California for the first time as an adult, something about the grit, the light, the color of the bougainvillea and orange poppies would remind me of home until bit by bit it became home in America.

Photos courtesy of the author.